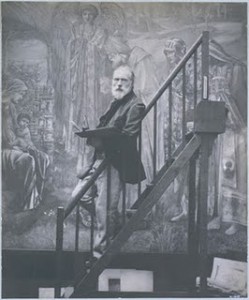

Masterpiece of Genius: Edward Burne-Jones

Edward Burne-Jones

Tate puts costly error on display

By Nigel Reynolds, Arts Correspondent

Four decades ago, the Tate Gallery could have bought Edward Burne-Jones’s huge final painting, The Sleep of Arthur in Avalon, for £1,000.

But the Victorian Pre-Raphaelites were despised and the gallery spurned the chance.

Now, the 21ft by 10ft painting is worth millions and on Tuesday Tate Britain welcomed it back – but only on loan.

Stephen Deuchar, the director of Tate Britain, admitted that his predecessors made a serious error of judgment.

He said: “There is not a shadow of a doubt that this is Burne-Jones’s late great masterpiece. These days it would be fought over.”

Burne-Jones spent 17 years on the canvas and he was still painting it on the day before his death in June 1898.

It is now owned by a museum in Puerto Rico and it is the first time it has been sent back to Britain.

Edward Burne-Jones – The Sleep of Arthur in Avalon 1881–98

The last and greatest work by Edward Burne-Jones, The Sleep of Arthur in Avalon(1881–98) returned to the UK from Puerto Rico for the first time in 40 years.

This enormous painting was loaned to Tate Britain along with Frederic Leighton’s masterpiece Flaming June (1895) by the Museo de Arte de Ponce, Puerto Rico, while its galleries undergo a major renovation and expansion programme during 2008.

The Sleep of King Arthur in Avalon was purchased for the Museo de Arte de Ponce in Puerto Rico by the island’s governor and founder of the museum, the benefactor Don Luis Ferré, in 1963. The vast canvas measures 2.79 x 6.50 m. Its transport to the UK and mounting for display at Tate Britain was a real challenge for conservators at both galleries.

De-installation in Puerto Rico of Edward Burne-Jones’ The Sleep of Arthur in Avalon Photo: © Museo de Arte de Ponce, Puerto Ricoenlarge

The painting is in oil on canvas and was started in 1881. Burne-Jones worked on it for 17 years; he even moved into a studio large enough for the purpose, but died before it was complete. While some areas are fully realised within the composition, close examination of the unfinished portions reveal that some of the instruments have no strings and figures have socks but no shoes.The canvas is made up of three pieces of cloth, and the two vertical stitched joins are visible when a light shines across the canvas from one side. The only way that this vast painting could be removed from its gallery and transported to the UK was by rolling the canvas. This operation was undertaken with the greatest of care to ensure the vulnerable joins and the turn-over edges of the paintings were not damaged.

The work was conserved in Puerto Rico sometime prior to travel. Its now fragile edges have been re-enforced and the whole canvas is glue-paste lined. The lining, (mounting a second canvas on the back of the original) was probably done when the painting was originally made, as added protection due to its overall size.

Its heavy-weight hardwood stretcher has eight vertical bars and three horizontal ones with keys and expandable joints allowing its dimensions to be increased slightly to take care of changes in the fabric such as sagging. The stretcher was taken apart and travelled in a separate crate with the frame which had also been dismembered for the trip.

Preparations for the arrival and re-stretching of this work involved all behind-the-scenes departments at Tate including Registrars, Art Handling, Frames Conservation, Conservation Technicians and Paintings Conservation. Four conservation technicians put the stretcher together and two frames conservators also got involved when the frame was reconstructed. Tate Britain registrars co-ordinated with a large team from art handling to have around eight art handlers manoeuvre the cases into the gallery space. Re-stretching had to take place right in the gallery as the work, once stretched again, could not be moved within the Tate due to its size. The floors were covered with protective materials to allow the painting to be unrolled face down.

Team of Art Handlers, Conservators and Technicians preparing to unroll the canvas at Tate Britain Photo: © Tate, London

nrolling took place slowly. To re-mount the painting conservators and conservation technicians worked opposite each other to tension the canvas and staple it at the reverse to its reconstructed stretcher.

The keys were tapped out at the end to improve canvas tension even further by expanding the stretcher size slightly once the canvas was already on. The real challenge occurred in bringing the work off the floor evenly and getting it upright without introducing distortion. It took a large team of highly trained art handlers to manoeuver the piece into position for re-framing.

Once fitted back in to its frame the careful process of raising and installing the work onto its supportive brackets could go ahead.

This Post Has 0 Comments