Genius of Picasso

Picasso was the first rock-star artist, whose wild visions gripped the public imagination and changed 20th-century art for ever. But his flamboyant personality divided opinion. Was he a playful genius, as some suggest, or a capricious and cruel misanthrope who left battered lives in his wake? On the eve of a new show in London, we speak to his closest friends and family in a bid to unravel the enigma.

“Picasso,” the surrealist poet Paul Eluard said, “paints like God or the devil.” Picasso favoured the first option. “I am God,” he was once heard telling himself. He muttered the mantra three times, boasting of his power to animate and enliven the visible world. Any line drawn by his hand pulsed with vitality; when he looked at it, a bicycle seat and its handlebar could suddenly turn into the horned head of a bull. But he also took a diabolical pleasure in warping appearances, deforming faces and twisting bodies, subjecting reality to a tormenting inquisition.

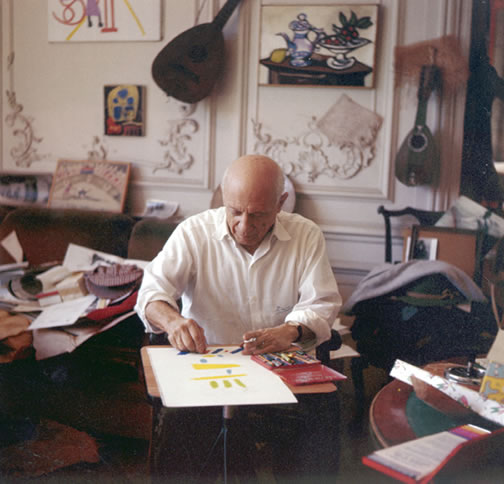

Picasso’s behaviour was equally dualistic. In my recent conversations with people who knew him, I heard him compared to a saint, and was startled when a former model took him at his word and equated him with God. His biographer John Richardson, who lived near him in Provence during the 1950s, told me about the warmth and rollicking conviviality of the man: the genius was also genial. Others described a predator who gobbled up visual stimuli and wolfed down friends, employees and lovers.

The Swiss dealer and collector Angela Rosengart, whose own Picassos are on display at her museum in Lucerne, remembered presenting him with some handmade drawing paper. He licked his lips as he appraised its possibilities: “I’m a paper-eater, you know!” he said. “People were happy to be consumed by him,” his daughter, Paloma, remarked. “They thought it was a privilege. If you get too close to the Sun, it burns you. But the Sun can’t help being the Sun.”

“Reality must be torn apart,” Picasso told Françoise Gilot, the young painter who met him in 1943 and, obeying his brusque instruction to prove her fertility, bore him two children, Paloma and her brother, Claude. After 10 years with him, Gilot wondered whether she, too, had been torn apart. As a painter and a sculptor, Picasso magically metamorphosed the things he saw; Gilot, in her book about their vexed partnership, felt that he had forced “a metamorphosis in my nature”. He remade her to suit himself, then looked elsewhere when she had served her purpose, which was to fuel his creativity and cosset his ego.

Unlike the rest of the many women in Picasso’s life, Gilot took the initiative by leaving him. She survived; others, less lucky, were, as Richardson says in his biography, “incinerated in the furnace of Picasso’s psyche”. His neurotically jangled mistress Dora Maar, the weeping woman in the paintings of the late 1930s, was skewered by his cruelty. At lunch, Richardson recalled, Picasso might praise a painting by Maar and liken it to Cézanne, giddily elating her; at dinner, he would casually remark that Cézanne was shit and drop her back into self-doubt.

Even after being replaced by Gilot, Maar was expected to remain available, forbidden to accept evening invitations in case Picasso whimsically decided to dine with her. She was not allowed to get over Picasso; his second wife, Jacqueline, a submissive helpmate but also a jealously protective guardian, could not forgive herself for surviving him. After his death in 1973, Jacqueline lapsed into an alcoholic fog, woozily communing with the spirit of the lord and master she addressed as “Monseigneur”. Richardson remembered her in the mid-1980s stubbornly asserting: “Pablo is not dead.” A year later, she shot herself.

The suffering has persisted into the second and third generations, as the miserable end of Picasso’s grandson Pablito demonstrates. The young man’s father, Paulo, was born during Picasso’s marriage to a Russian ballerina; emasculated and shiftless, Paulo served for a while as Picasso’s chauffeur. Pablito, whose name marked him as a further diminutive of the glowering paterfamilias, tried to pay homage to Picasso the day after his death; the monopolistic Jacqueline had him expelled from the villa and decreed that he and the rest of Picasso’s motley brood could not attend the funeral. Heartbroken by this rejection, Pablito downed a bottle of bleach. His sister, Marina, who has published a memoir denouncing their distant, coldly manipulative grandfather, found Pablito haemorrhaging his corroded intestines: talk about reality being torn apart!

Jacqueline nudged Richardson to begin a biography, counting on him, as he said when we met in New York, to be “discreet”. The undertaking has been a devotional act. Richardson began to worship Picasso when he first saw reproductions of his work in magazines during his schooldays in the late 1930s. “From the age of 13 to 15, I was obsessed by Picasso – and 10 years later I became his friend!”

They met while Richardson was living with collector Douglas Cooper in a chateau they elaborately restored; the two men belonged to what Richardson calls Picasso’s “tertulia”. “That’s the word Spaniards use to describe a group of guys who meet in the cafe to discuss politics, women, sport. We didn’t exactly do that. Most often, Douglas and I cooked dinners for Picasso and his entourage on their way home from the bullfights in Arles. Picasso often repaid our hospitality by bringing us drawings, though later he gave us caviar instead; he joked that now the prices for his art had risen so high, caviar was cheaper!”

What Picasso demanded from his gang of companions was, as Richardson put it, “fealty”. It is a revealingly antiquated word, remembering the vassal’s obligation of fidelity to his feudal overlord. But can a biographer be so subservient?

“I’m sure Picasso would have hated my books about him,” said Richardson. “He was secretive, he didn’t want everything to be known. His affairs were the source for his work. Once, when he was showing me some portraits, he said, ‘It must be awful for a woman to look at the way I paint her and see that she’s about to be replaced.’

“He did everything in his power to block the publication of Gilot’s book in 1964 and when he failed he banished Paloma and Claude as revenge on their mother. Sometimes, the truth is unpleasant, but I don’t hold with the way he’s been demonised by feminist academics – denounced as a wife-beater and all the rest.” It was only too easy for Merchant and Ivory to cast Anthony Hopkins in Surviving Picasso, their slushy film about his relationship with Gilot; they relied on Hopkins to bring to the character the gloating, carnivorous guile he found in Hannibal Lecter.

“Picasso could be ferocious,” said Richardson, “but he was also gentle, sweet, child-like. Dora Maar used to talk about his persecution of her, but when she had a breakdown and got religion, she took to calling him the apostle who regenerated art. After all, she’d been the mistress of Georges Bataille, the most way-out of the surrealists, a real satanist, in love with evil and erotic pain. So life with Picasso must have been a bed of roses after the bed of thistles she shared with Bataille!”

Richardson has likened Picasso to Frankenstein, who, defying God’s creative primacy, soldered corpses together; his portrait of Gertrude Stein, for instance, grafts on to her mask-like head the face of a nonagenarian smuggler Picasso met during a Spanish holiday. “He had a Dracula side as well,” Richardson told me. “He fed on those around him, like a vampire sucking life out of his victims. He once said something very telling about the fans, stalkers, autograph-seekers, dealers, collectors and paparazzi: ‘These people cut me up like a chicken on the dinner table. I nourish them, but who nourishes me?’

“We all donated our energy, if not our blood. If there were six or eight people for lunch, he’d get every single one – he’d seize control of you, turn you inside out. The pretty girls he’d flatter and flirt with. If there were kids present, he’d make toys for them or do drawings. Even animals weren’t immune – he’d entice them to come to him. Everyone had to be seduced. You ended the day completely drained. But he’d imbibe all that stolen energy and stride off into the studio and work all night. I can’t imagine the hell of being married to him!”

Douglas Cooper fell from grace after he presumed to plead the cause of the excommunicated Paloma and her brother. “That was absurd,” said Richardson, who re-enacted the scene for me with a satirical glee. “Nothing could have infuriated Picasso more than trying to get him to recognise his illegitimate children as heirs – not for financial reasons, but because any mention of a will reminded him of death, which his art was so determined to deny. Douglas was thrown out, but wouldn’t give up. There was a steep flight of stairs leading down from Picasso’s villa to the front gate and poor Douglas paused on every step, kneeling and weeping and grovelling and begging to be forgiven! It did him no good at all.”

Richardson felt Picasso’s muffled annoyance only indirectly. “It was because of something I wrote for the Observer, which he read in the French equivalent of the Reader’s Digest. It was about his friendship with Braque and I mentioned that Picasso had offered him studio space at his place in Cannes, which Braque refused. Trivial enough, but it made him cross because he didn’t want it known that anyone could say no to him! He never referred to it; Jacqueline ticked me off on his behalf. I did once see him being mean, when he turned up with Cocteau and all the hangers-on for dinner after a bullfight. Jacqueline looked ill, collapsed and I carried her upstairs. Picasso just shrugged and said, ‘I seem to have a corpse on my hands.’ She told me that she needed an operation – a hysterectomy, I suppose, though she was too ashamed to use the word – but couldn’t have it because, ‘Pablo doesn’t want to live with a eunuch’.”

The remark poignantly acknowledged Jacqueline’s sense of her duty (and of her failure to fulfil it, since she did not add to Picasso’s eclectic crop of children). He was a creator; his women had a lowlier responsibility, serving as reproductive vehicles. “Of course,” Richardson added, “it was just the idea of having offspring that appealed to him. In practice, he expected the current woman in his life to be at his beck and call, so he begrudged time spent on maternal chores. He could be a doting father. He loved devising games, teaching them to draw, romping on the beach. But his work had priority and then he didn’t want to be bothered.”

The purpose of women was clearly defined. What, I wondered, was the role of male admirers like Richardson? Did the master expect his companions to be slaves or, at least, feudal vassals? I asked about Picasso’s assertion that “to like my paintings, people really have to be masochists”. “He probably said that for effect,” Richardson retaliated. “A day later he’d have been saying the opposite.” But another anecdote made me wonder about the psychodynamics of their association. Picasso often showed the young man sets of drawings, asking him to choose the best – significantly “le plus fort”, never “le plus beau” – and always accepting his judgment.

“I was so amazed by his interest in what I felt that I got teary-eyed! When it happened more than once, I began to suspect he was playing a trick on me, so I asked, ‘Hey, Pablo, what’s up?’ He said, ‘There was only one other person I could make cry like that.’ I badgered him to tell me who it was and then he changed the subject because he’d given away too much.”

The other lachrymose acolyte was Georges Bemberg, the unstable son of a brewing tycoon, who claimed to be Picasso’s protegé. When he went mad, his family covered its embarrassment by pretending that he was dead. Almost 50 years later, Picasso was asked to sign some drawings that Bemberg had owned. He reacted to the imitative doodles with horror and superstitious alarm, yelling: “Don’t touch them, they’re the drawings of a madman!” Picasso enjoyed adoration, but reviled followers who drew too close to the sacred fire.

Richardson has so far survived Picasso, but the race is not yet over. He has spent almost 40 years on the biography, though the three volumes published so far have only reached the middle of Picasso’s life. “I’m 85 and I don’t have all that much time. The biography grew at its own pace, which is why it has taken so long. There has to be a fourth volume, maybe a fifth – who knows? I suffer from wet macular degeneration and I need an injection in my eyeball once a month. I’m fine in front of paintings, but I have a problem with print, so research is hard.”

The contrast with Picasso’s ebullient, often riotously obscene, old age is clear enough. Angela Rosengart told me, with some genteel euphemisms, about a conversation she overheard between Picasso and the equally ancient pianist Artur Rubinstein. She at first described the talk as “boyish”; when I pressed her for details, she said: “Oh dear, they were telling their dreams and they were so indecent!”

Genius, for Picasso, was lecherous adolescence recovered at will. Richardson is less frisky, but keeps going with a gallant, generous stoicism. He is currently preparing a New York exhibition of Picasso’s last works – paintings of a muddled rabble of musketeers, whores, thieves and beggars, with faces scavenged from Rembrandt, Velázquez and Goya. “By the end of his life, he knew he couldn’t compete with the avant-garde. Americans had taken over, bringing back the abstraction that he always despised. But he turned the studio in his last house into a microcosm, projected slides sent from the Louvre on the walls, and shut himself away to cannibalise the entire history of art. It was a triumphant end to his career, not a falling-off.”

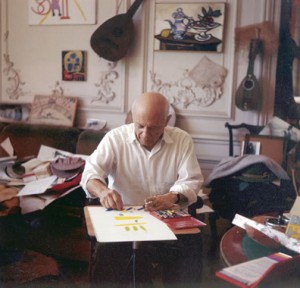

I couldn’t help comparing the clutter of Picasso’s working space, strewn with relics, fetishes, props for his dressing-up games and the dung of his pet goat, with the gilded trophies and pedestalled neoclassical busts in Richardson’s princely pad at the bottom end of Fifth Avenue. The artist, working like a cyclone, throve in chaos; his biographer, with a tidier mind, is slowly imposing order on Picasso’s rackety life and refuses to rush to judgment before his knowledge of the subject is complete. I hope the tortoise catches up with the hare at the finishing line.

When we met in Lausanne, Paloma Picasso told me about being present, as a quiet and unobtrusive child, during sessions of almost frenetic creativity in the studio. “He was 67 when I was born, but I never thought of him as old. He was so vital, so playful. Perhaps he thought of me as a contemporary, even though I was only four when my mother took my brother and me away to live in Paris in 1953. He was proud to draw like a child, not someone with an academic training.

“One day, I got a pair of white espadrilles. I was so happy, they looked so cute, I’d wanted them so much. And the moment my father saw them he covered the canvas with red and blue designs. They looked fabulous, they’d become an art object, but it was a little sad too; I realised I’d never ever be able to have white espadrilles like the other girls!”

Even when taking a rest or pausing to entertain his daughter, Picasso could not help littering the world with more art. “All day long while he worked, he smoked – first Gauloises, then Gitanes. The cigarettes came in little cardboard cartons and whenever he finished a packet, which was three or four times a day, he’d cut it up to make me a doll or a finger puppet or scribble a pencil drawing on it. He couldn’t stop himself.”

Angela Rosengart remembers a similar overflow of inventiveness. Arranging for her to visit him next day with her father, Picasso drew them two tickets of admission, decorated with a sketch of Rembrandt and a scribbled signature. They gained entry to Picasso’s presence by showing these little Picassos (which they were allowed to keep).

Jean Cocteau thought that Picasso had “terrible eyes that pierced like gimlets”; Richardson thinks of him as a witch doctor with the gift of x-ray vision that Andalusians call the mirada fuerte – a strong gaze that penetrates objects. The black eyes inherited by Paloma are less baleful and they shone with delight as she remembered a world in which daily reality consisted of dreams and games.

“We had a menagerie in the house. My father was like St Francis of Assisi – animals couldn’t resist his aura. A goat called Esmeralda had the run of the villa, it lived upstairs with us. My mother gave away an earlier Esmeralda to some gypsies because she hated its smell and the mess it made; my father was outraged and said he loved the goat like a child. He even sculpted it, with cardboard ears, a basket for its belly, udders made of terracotta milk jugs and a metal pipe sticking out for its anus. This one was the second Esmeralda and it was lonely. It cried at night and I’d go and goat-sit to comfort it. Often, I fell asleep beside it.

“One summer, a frog hopped out of the pond and came and sat with us on the steps in the evening when it was cool. My father constructed a little ladder so it could climb up and get into the house. We gave it a bowl to live in, but it couldn’t feed itself in there. My father collected flies for it; he had a way of gently sweeping the air with his open hand and then closing it on the insects. Even the flies weren’t afraid of him!”

Paloma illustrated the gesture for me, but the clatter of her gold-bangled wrist and the flash of her jewel-studded fingers would have scared off any swarms. Even so, I saw what trust her father must have had in the strength and stealth of his hand, which he relied on to make instantaneous decisions about marking canvas or modelling clay.

During the 1950s, Paloma and Claude travelled down from Paris to the Midi to spend their holidays with Picasso. “He played the role of father when he met the train and asked us about school. But he really didn’t care and admitted that he’d been a bad student himself. His father was a colombophile who allowed him to take his doves to school and you can imagine how that disrupted lessons! By the end of the day, our games would resume.”

The idyll ended with the publication of Gilot’s Life With Picasso in 1964. Rosengart remembered his reaction when he read the French translation. “He gripped my shoulder and said, ‘How could a woman do such a thing?’ That shows, you see, what respect he had for women!”

I begged to differ; the remark called Gilot a disgrace to her gender because of her independence. When Picasso first met Gilot, he’d proposed keeping her captive in an attic, swaddled like a Muslim woman, until he was ready to unwrap her for delectation; early in his friendship with Rosengart, he said that he fancied detaining her on the premises as a perpetually available model.

“The book was not harmful,” Paloma insisted. “The art world deified my father and my mother wrote about him as a human being – about his little quirks and superstitions, but also about his attempts to control her. Anyway, Jacqueline used the book as the excuse for a breach with us. From now on, we officially didn’t exist, we couldn’t be mentioned, we were bad. But how evil can you be when you’re only 14? Maybe Jacqueline resented us because she gave him no children.

“Once, during the time we were banned, I saw my father in Cannes. I rushed up to him, we embraced as if nothing had ever happened. Should I have told him that I’d been to the house every day that week, but was not allowed in? I didn’t want to ruin the moment with accusations. Then Jacqueline bustled up and bundled him into the car. She must have been very insecure, which is maybe why she couldn’t survive him.”

Picasso died intestate, forcing Paloma and Claude to apply to the French courts for recognition as his descendants and heirs; eventually, a legal ruling allowed them to adopt the surname Ruíz-Picasso. The hyphen ironically disinterred the conflicts of previous generations. Ruíz was their father’s patronymic, which he spurned as a means of separation from his own father, a tamely realistic painter; he called himself Picasso after his mother’s family.

But the famous name that Paloma coveted carried its own burden. “Both my parents were artists, so what else could I be? When the estate was settled, each of us – me, my brother and the step-siblings from other relationships – was allowed to choose a group of his works, within certain financial limits. And then we were involved in setting up the Musée Picasso in the Marais, which took care of the death duties. After you’ve been looking at Picassos all day, you don’t want to come home and pick up a pen or a brush! Although I started to design jewellery before he passed away, for a long while I felt inhibited. How could I measure up?”

She soon found an independent way to merchandise the family brand, and, following the example of the ceramics her father turned out in multiple editions in the 1950s, supplied the market with her own relatively affordable Picassos: jewellery, cosmetics, leather goods, sunglasses, china, tiles, furniture covers and wallpaper. Her father, to keep from being idle, sometimes manufactured such accessories. A couple of years before his death, he spotted a brass pendant dangling from Angela Rosengart’s belt. He asked to borrow it and kept it for months. Long after she’d resolved to forget about it, he returned it gilded and engraved with the head of a baroque cavalier and personally dedicated to Rosengart.

Paloma’s cheekiest allusion to Picasso’s legacy is the men’s fragrance she called Minotaure, launched in 1992. The randy bull was one of his self-images and he often drew the horned Minotaur trampling sacrificial virgins beneath its hooves. Paloma’s imaginary beast is sweeter-smelling, less rapacious: “I was thinking of the Mediterranean and of that scented darkness when I chose the name. It’s an indirect allusion to my father, but it shows how inescapable he is!” Richardson’s biography argues that the purpose of Picasso’s art is exorcism, the casting-out of evil, achieved by the black magic of his deformations. Paloma’s perfume manages a milder exorcism of her father’s influence, transforming the musky odour of rut into a gentler, more fetching olfactory aura.

Psychologically, Paloma also learnt from his example. Paparazzi besieged the hospital in which she was born and dispatched nurses to bribe her mother; her infancy and childhood were remorselessly documented, since Picasso, as Richardson said, was “as famous as a rock star”.

Richardson regretted Picasso’s antics for the camera. “He played the fool, dressed up, performed little mimes, though often it was his only way of communicating with people. After the war, it was compulsory for Americans visiting Paris to call on him. They spoke no French, he spoke no English, so he had to put on these foolish dumb shows with silly hats or Indian head-dresses, like the one Gary Cooper gave him.”

Paloma took a different, wilier view. “My father didn’t deny his celebrity. He treated the press the way you would do a dog – if you run away, it will chase you and bite you, but if you play with it, it may lick your hand.” Paloma developed her own sly version of this tactic and, like her friend Andy Warhol, she became socially and commercially ubiquitous while remaining unknowable.

“I was so timid,” she sighed. “That’s why I played the part of that lustful lesbian Hungarian countess in the film Immoral Tales; I thought that would cure my shyness! When I began designing, I diverted attention to my persona, to the extravagant way I dressed or the fire-engine-red lipstick I wore. The look was a mask like those my father collected and I hid behind it.”

Her current disguise is an immaculate anonymity. Sitting opposite me on a sofa in the Lausanne hotel, she could have been any prosperous, well-tended Swiss matron, except when the gold hoops rattled on her wrists and her father’s eyes scorched me like a pair of black suns. More than 50 years after she first posed for Picasso, Angela Rosengart recalled with an excited shudder the raking scrutiny of those eyes. “They burned,” she said. “He ate me with his eyes; you could feel him swallowing whatever he looked at. It was terrifying, exhausting, to sit there for two hours being looked at in that way, as if he were shooting arrows into me. I only really understood it much later when I read in John Richardson’s book about the mirada fuerte.”

Richardson, I noted, calls that unblinking gaze “an ocular rape”. “No, I never felt threatened,” said Rosengart. “Picasso was always so kind to me, so tender. And my father took photographs throughout the sessions, though he had to do so from the next room. First, Picasso made a pencil drawing, then next time a linocut, later a lithograph and aquatint – the same face, but always in a different medium, which shows how he liked to change people as he worked on them.

“I would never have asked him for a portrait. Helena Rubinstein did that. She annoyed him so much that finally he gave in and did a whole series of drawings. They made her look so horrible that he never showed them to her.”

Rubinstein, the magnate who invented anti-wrinkle creams, appears in Picasso’s sketches as a cadaverous crone with gnarled, bejewelled knuckles; Angela Rosengart, so deferential and undemanding, looks wide-eyed with joy and gratitude in his portraits of her. “A Spanish art critic told me that Picasso’s first little girlfriend was called Angela and I remember once when he introduced me to someone he said, ‘Elle s’appelle Angela’ and repeated the name as if he was caressing me. Perhaps I was a souvenir of that first love – an innocent one, I hope! Anyway, that’s how I crept into immortality through the back door.”

Another young woman inadvertently immortalised by her brief contact with Picasso was 19-year-old Sylvette David, who posed for him in the summer of 1953. She caught his eye when her boyfriend tried to sell him some shakily assembled cubist chairs; soon she was visiting the studio every day.

David – today called Lydia Corbett after a failed second marriage to an Englishman and a rebaptism following her religious conversion – lives in rural Devon. Stark trees in mucky fields creaked as gales lashed them, ragged clouds hurtled across the sky and rooks screeched imprecations. “Provence is nicer, non?” said the erstwhile Sylvette as she surveyed the unmeridional weather.

Picasso fancied Sylvette because she had a ponytail. “He was fascinated by that. It was my father’s idea; he liked the way ballerinas pulled their hair back. And no one ever had such a high ponytail as mine! Even Brigitte Bardot decided to copy my hair when she saw me on the Croisette in Cannes. Of course, she wasn’t naturally blonde, like me!”

Sylvette’s fetishistic handful of hair has gone, replaced by Lydia’s long yellow bangs. As a remembrance of the ponytail, however, she had twined a few strands into braids, with red wisps of ribbon knotted around them. “It is the colour of the passion of Christ,” she told me, fingering the ribbon. Then, less mystically solemn, she added: “My grand-daughter likes to pull my braids.” Was this, I wondered, a dare?

Françoise Gilot, preparing to walk out on Picasso in 1953, thought he was using Sylvette to make her jealous and scoffed at his claim that the girl had “very pictorial features”. My view is that the ponytail lifted her face, pulled the skin taut and revealed sculptural planes.

Picasso began with delicately accurate sketches of her, then in the next few months experimentally racked and twisted her body, finally remaking her in folded metal or casting her in bronze as his Woman With a Key, a statue originally pieced together from fire-clay bricks and other implements from a potter’s kiln.

A monolithic Sylvette, with her adamantine ponytail set in concrete, stands in the grounds of New York University, inflated from Picasso’s original by Norwegian sculptor Carl Nesjar. “Ah,” said Lydia, showing me a dogeared photo album, “I have never seen it, no one invites me to New York! Could you write that I would like to go?” If my hair had been braided, I’m sure I would have felt a persuasive tweak.

Lydia looked back with a teasing grin on the erotic imbroglio that surrounded Sylvette. “I was in the middle of two women – Françoise and Jacqueline – and they didn’t like me being there. Oh là là, it was difficult! Picasso often painted me in a rocking chair. You see it again in his portraits of Jacqueline, but I sat in it first! After a while, she made sure I wasn’t welcome. Finally, she presented me with a book about his art, which he inscribed to me. That was her way of saying, ‘It’s over, go.’ She had no need to worry; I was very pudique, not like the girls today.

“Later I heard that the statue of me as the woman with the key was called The Brothel-Keeper and I was so offended. Who would say that about me? Maybe Jacqueline! Once he did offer me money to pose, but I refused. I thought, what if he wants me to be nude? He was 73 then, he wore slippers. But he was clean, he had no whiskers and he smelled nice, not of wine and garlic! He went back to his youth through me. He gave me a cuddle sometimes, like a good old dad.”

I was not so sure, listening to Lydia’s account of Sylvette’s induction, that Picasso’s intentions were paternal. He took her to his bedroom and bounced encouragingly on the bed. Instead of following his example, she marvelled at the agility of his ageing limbs. Then he led her to the stables, where his favourite Hispano-Suiza limousine was housed.

“He opened the back door of the car and said, ‘Come in.’ I thought, ‘That’s a bit funny’, but all we did was sit there, with an imaginary chauffeur in the front. We just talked.” About what? I asked. “Oh, he told me that creativity was happiness, other things like that. His Spanish accent was so strong, often I couldn’t understand what he was saying!”

Despite Jacqueline’s rebuff, Sylvette survived Picasso. Indeed he subsidised her after-life by presenting her with one of his 40 paintings of her, which she sold to buy an apartment in Paris.

An illustrated children’s book by her friend Laurence Anholt narrates her story as a fable of rebirth: Sylvette, surveying the Eiffel Tower from an eyrie paid for with a Picasso, embarks on an artistic career with the old master’s encouragement and also manages, thanks to his avuncular ministrations, to overcome the trauma of abuse in childhood by her mother’s bullying lover.

Divine intervention also did its bit. “After my first husband betrayed me, I was so hurt, so destroyed. But suddenly I was surrounded by a light, I felt happy, and I started singing in Latin about the pure in heart. That was God’s gift to me!” Another exorcism had occurred, this time with the aid of celestial grace, not Picasso’s demonic conjuring.

It is fitting that Picasso’s place in Sylvette’s life was taken by the only creative force he viewed as an equal. “Ah oui,” said Lydia, fingering the ribbon that was her memento of Christ’s blood, “perhaps God sent me to Picasso to cheer him up and sent him to me to heal my hurt. God is in everybody. Those dark eyes Picasso had – that was God looking at me!”

She showed me one of her recent watercolours, influenced more by Chagall than by Picasso. Against a gold background like that of a religious icon, Sylvette floats among a collection of Picasso’s props – owls, masks, statuettes – with a cowled monk representing his better self; the painter’s round face is lunar and those omniscient eyes keep protective watch on the world. “He’s so big he envelops us all,” said Lydia, as if he were about to materialise in the room.

I wondered, however, why she had given Picasso three arms, which reach out to pinion the airborne Sylvette. His extra, exploratory hand seemed bent on mischief. Was Picasso a deity or a randy old devil? Or perhaps, as Eluard suggested, both at once? According to John Richardson: “The man was a paradox. Whatever you say about him, the reverse is also true.” His lovers, friends, models and children know that he metamorphosed them. Whether they were recreated or destroyed, even they can’t be sure.

• Picasso: Challenging the Past is at the National Gallery, London, 25 February-7 June, sponsored by Credit Suisse.

• John Richardson’s A Life of Picasso, Volume III: The Triumphant Years 1917-1932 was published in paperback last week.

It’s a shame you don’t have a donate button! I’d definitely

donate to this outstanding blog! I guess for now i’ll settle for bookmarking and adding your RSS

feed to my Google account. I look forward to fresh updates

and will share this blog with my Facebook group.

Talk soon!