Is it fake or is it Rembrandt’s nudes?

Is it fake or is it Rembrandt?

Over the years there has been considerable controversy over unsigned drawings that seem to be from the hand of Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn, the Dutch painter and etcher who died in 1669.

Since 1968, participants in the Amsterdam-based Rembrandt Research Project have halved the accepted list of genuine, “autograph” paintings by the master to about 300 pictures. (They also elevate new works to the list from time to time.) There are about 300 accepted first-state etchings.

An exhibit at The Getty makes an effort to distinguish the real from the ersatz. Fifty-three of the small drawings on display are now generally presumed to be by Rembrandt. The remaining 50 have been reattributed to 14 of his presumed pupils.

Reviewer David Littlejohn writes:

As a rule, the curators (from Amsterdam, Los Angeles, Berlin and Cambridge, Mass.) look for things like variation in line width, a great range of strokes, a prodigal use of white space, a lack of finish, a concern for evoking the play of light and depth of space, a unity of composition, and striking emotional effects in deciding whether a drawing is by Rembrandt or one of his followers.

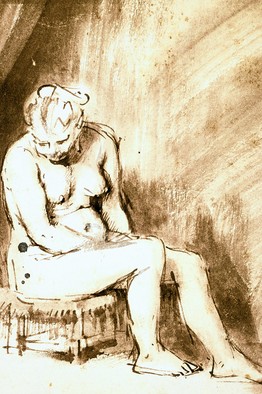

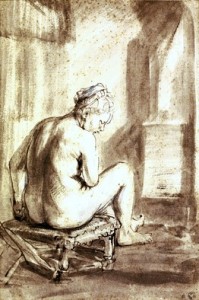

The most powerful near-exact pairing may be two brown ink and wash drawings—one by Rembrandt, the other by Arent de Gelder—of the same pudgy nude woman seated on a low stool, her head bent and eyes downcast. De Gelder draws the model with her back to us, her head and torso turned right. He pays close attention to her coiffeur and facial features, and brushes in the vaulted chamber in which she sits:

Rembrandt has her facing us, her imperfect body and face roughly outlined, her hands in her lap and face bent down as if in sorrow or shame. The space around her is just darkly stroked wash, as if to emphasize her existential plight. He even leaves in dropped spots of ink and redrawn lines. De Gelder’s is an attempt at a real depiction of the woman. Rembrandt’s is minimalist, knowing, evocative and expressive.

Littlejohn writes of “the profound emotional power Rembrandt could achieve with just a few lines.”

Rembrandt emerges once again as the most humane and sympathetic renderer in history of individual human beings. His faces are so compelling because he cares so about the people behind them. He remains the master of the dramatic play of light (in these cases, blank paper) against dark, the vivid contrast almost always expressive of something. His compositions—of fingers, veils, bodies, crowds, whole scenes—almost always seem intuitively right.

What his drawings reveal that his etchings and paintings do not is what a modern or Japanese-style minimalist he could be, satisfied to render much of his vision through a few scribbles or broad, rapid sweeps of the pen or brush. None of his pupils had the self-assurance to risk that.

This Post Has 0 Comments