An amateur artist who pulled off the world’s most audacious Art Fraud

The true story of the downfall of an amateur artist who pulled off the world’s most audacious art fraud

By LANEY SALISBURY

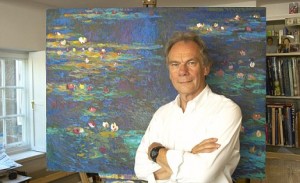

Myatt poses in front of his ‘Monet’ paintings

The experts gathered at London’s Tate gallery watched in appreciative silence as two white-gloved curators carried the museum’s latest acquisitions into its boardroom.

Paintings of birds by a highly regarded but little-known Fifties French artist named Roger Bissiere, they had been donated by Professor John Drewe, a distinguished scientist and businessman.

On that April afternoon in 1990, everything about Drewe suggested that he was a gentleman of style and substance, from his pencil-thin moustache to his expensive suit. His bequests, however, were not all they seemed.

Far from being the modern masterpieces Drewe claimed, they had, in fact, been painted just two weeks earlier, using ordinary household emulsion and framed with wood left over from building work at his home in North London.

These fakes were key to what Scotland Yard later called the biggest art fraud of the 20th-century – a multi-million-pound scam which saw hundreds of forgeries sold to highly respected museums, galleries and collectors across the world.

The only consolation for Drewe’s victims was that they were not alone in being deceived – for Drewe was one of the most plausible conment of recent times, which I reveal in a new book about the daring fraud.

A compulsive but utterly believable liar, he often told people that his father was a scientist. In truth, he was the son of Sussex telephone engineer Basil Cockett and his wife Kathleen.

Born in 1948, he left school when he was 16 and began working as a clerk at the Atomic Energy Authority, only to resign at 19 and disappear without trace for the next 15 years.

No one knows exactly what he did in that time, but he no doubt relied on his astonishing ability to absorb information on any given subject and regurgitate it so authoritatively that people believed he was whoever he purported to be.

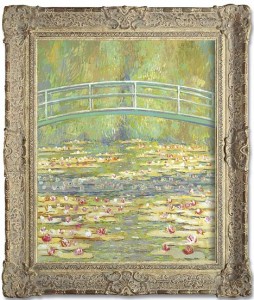

Replica: The ‘Monet’ painted by convicted forger Myatt

At various times in later life, he claimed to be an agent for the Israeli secret service, a consultant to the Ministry of Defence and even an inventor of James Bond- style gadgets, including a chemical warfare suit that folded to the size of a golf ball.

In 1980, while attending a party as nuclear physicist Professor Drewe, his most enduring persona, he met Bathsheva Goudsmid, a 34-year-old eye doctor who would become his common-law wife and, later, one of his victims. She was then already pregnant by a former boyfriend and, after the birth of her son, Drewe moved in with her.

‘You can make a decent living at this. It’s yours if you want it’

Not long after, they had a baby daughter and eventually he suggested that they buy a house together in Golders Green, a wealthy Jewish neighbourhood in North London.

Somehow persuading her that she should take out a large mortgage in both their names, he promised to pay his share once a fictitious inheritance came through.

But Drewe was also about to find a real, and very lucrative, source of income in John Myatt, a failed 41-year-old artist who had first been inspired to start painting after seeing Claude Monet’s La Grenouillere as a student in 1971 – and would become his reluctant accomplice in the scam.

Living in a rundown farmhouse in rural Staffordshire and struggling to bring up his two young children after his wife left him for another man, Myatt needed to augment his earnings as a part-time art teacher.

As a painter, he had an innate ability to ‘stand in someone else’s shoes’, as he described it. Falling into an empathetic trance as he approached a canvas, he produced works which could easily pass as undiscovered gems by the artists (such as Monet, Picasso and Ben Nicholson) he emulated.

In 1986, he placed an advert in Private Eye, offering ‘genuine fakes’ of pieces by 19th and 20th-century masters. This was an entirely legitimate business, Myatt making it clear that the paintings were his own.

But then he received a phone call from a well-spoken man introducing himself as Professor John Drewe.

He said he had bought a new house and wanted to decorate it with paintings in the style of the French artist Henri Matisse and the Swiss-German Paul Klee.

Over the next two years, Drewe became Myatt’s most important customer, buying some 20 different paintings which, unbeknown to him, were sold on to unsuspecting dealers as the work of the famous artists concerned.

Aware that Myatt would eventually realise that he had ordered far more paintings than could ever fit into his home, Drewe waited until his dupe was at his most defenceless before taking the plan a stage further.

Although he was making a fortune from the paintings, he paid Myatt so little that he could hardly provide for his children. Following a visit from a social worker, Myatt confessed to Drewe his fear that they might be taken away from him.

Far from being modern masterpieces, they had, in fact, been painted just two weeks earlier, using ordinary household emulsion

That was Drewe’s opportunity to reveal that he had taken Myatt’s latest work, an imitation of French artist Albert Gleizes, to Christie’s where it had been accepted as genuine and fetched £25,000 at auction.

‘You can make a decent living at this,’ Drewe said, handing Myatt a fat brown envelope containing half the proceeds. ‘It’s yours if you want it.’

Myatt took the cash, reasoning that it would tide him over until he could find a legitimate source of income. But while he tried to salve his conscience by giving some of these earnings to a church, the guilt preyed on him.

Paranoid that a neighbour might drop in and see him at his easel, he painted only at night and lived in constant fear of being exposed. Even so, he and Drewe showed an extraordinary parsimony in their fraud.

Concentrating on modern works because it would be too expensive to buy the ingredients found in the old master’s pigments, they cut costs further by mixing ordinary emulsion paint with turpentine and linseed oil.

With the addition of KY lubricant jelly, which made it flow easily across the canvas, this was apparently indistinguishable from modern oils. A smearing of dust from a vacuum cleaner bag gave the finished artworks an authentic, weathered look.

All that remained then was to provide them with a ‘provenance’, a collection of receipts, old exhibition catalogues and other documents which demonstrated a painting’s history beyond question.

Myatt poses with actress Jane Horrocks and her portrait for television programme Brush With Fame

While potential buyers were presented with photocopies of these documents, the originals were often held at the major museums and galleries. But Drewe came up with an ingenious idea.

Organisations were constantly on guard for people removing material from their files, but who would suspect that someone would want to put documents in? And so by inserting false credentials for Myatt’s paintings into these records, he could lend them instant and impeccable pedigrees.

His plan was soon in motion. Posing as a wealthy art collector and travelling around London in a chauffeur-driven Bentley, he organised lunches at Claridge’s for senior art figures including Sarah Fox-Pitt, an aristocrat in her 40s who was the notoriously fearsome gatekeeper of the Tate’s archives.

Despite her formidable reputation, Fox-Pitt was impressed by Drewe’s claim that his father invented the atom bomb and was reeled in by his promise to give his Bissieres to the Tate, along with a substantial donation of £500,000 towards the upkeep of the archives.

In prison Myatt earned the nickname ‘Picasso’ by doing portraits of other inmates in return for phonecards

There was just one hitch. When Myatt realised that Drewe had given the Tate the Bissieres, he insisted that he ask for them back, claiming they were among his poorest works.

The Bissieres might pass muster on the open market, he argued, but the Tate was one of the world’s most prestigious museums and it would be mad to try to fool its curators.

Even after Drewe retrieved the Bissieres, and offered an extra cash donation of £20,000 in their place, the Tate suspected nothing untoward. And by the time it realised that the original half million it had been promised would never materialise, it was too late. Drewe had already been given access to its archives.

Ostensibly researching the history of London’s Hanover Gallery, which sold many paintings by the Swiss artist Alberto Giacometti during the Fifties, Drewe slipped into its files forged documents relating to a painting in his style called Standing Nude.

All seemed to go well but, unbeknown to him, this naked woman would eventually play a part in his downfall.

Myatt had struggled with the picture from the start. Unlike Giacometti, whose wife often posed for him, he was too fearful of discovery to invite a real model into his studio. Instead, he had tried to imagine a nude female standing in front of him.

This worked surprisingly well but, for some reason, he could not get the feet right. He asked for more time, but Drewe insisted he paint a table in front of them and, despite his misgivings, took the picture away to be sold.

Myatt’s concerns appeared to have been unfounded when Sotheby’s agreed to put the picture up for auction with a price estimated at £180,000 to £250,000. Unbeknown to the fraudsters, however, the auction house routinely sent its catalogue to the Giacometti Association in Paris.

This was overseen by Mary Lisa Palmer, a determined American who had devoted many years to preserving Giacometti’s legacy and knew that he would never have ruined a composition by inserting a table in this way.

Her disquiet grew when she visited the Tate’s archives – which store details on paintings, even if they have never been shown there – and asked to see the supporting documentation for the Standing Nude.

It included a black and white photograph which, to her trained eye, looked slightly too sharp. She guessed correctly that it had been added to the files only recently.

Since Drewe was known to have handled these materials regularly in the previous months, he seemed the most likely culprit. But the Tate refused to investigate – arguing that they could not risk alienating an important donor on what seemed a mere hunch.

Undeterred, Palmer persuaded Sotheby’s to remove Standing Nude from sale. She asked for the suspect picture to be sent to her for closer inspection, but the auction house returned it to Drewe instead. In the coming years, however, she looked for other evidence against Drewe, finding a number of other Giacomettis which gave cause for concern.

In each case, the paper trail pointed to his involvement and suggested that he had compromised the archives not just of the Tate but other national institutions, including the Victoria & Albert Museum, the Institute of Contemporary Arts and the British Council.

With their unwitting help, he would pass off hundreds of other fakes as the work of modern masters, including the French painters Nicolas de Stael and Georges Braque, and the English artist Graham Sutherland.

Although these figures were not household names, Drewe may have pocketed millions of pounds from sales and could have made more, if not for his increasingly strange behaviour in the early Nineties.

In 1993 he left Bathsheva Goudsmid for another woman, claiming falsely that Goudsmid was mentally unstable and had put their pet goldfish in the microwave before throwing scalding water on their dog.

His supposed standing in the academic and scientific communities won him custody of their children and she almost lost her job because of the accusations. But she would eventually have her revenge.

In September 1995, she drove to her local police station with two black binliners which she had discovered in her attic. Each was filled with hundreds of documents connected to the forgeries.

When the police visited the Tate archives as part of their subsequent investigation, they learned of the concerns raised by the Giacometti Association over the past few years.

Mary Lisa Palmer had never found quite enough proof to take action against Drewe, but finally her evidence about the Standing Nude and other pictures would play an important part in bringing about his arrest and subsequent conviction.

Released in 2000, after serving four years of his six-year sentence, he continues to maintain his well-rehearsed role as a citizen above suspicion, still maintaining that he is a physicist and insisting that he was framed as part of a Government conspiracy.

As for John Myatt, the officers who arrested him reported that he seemed almost relieved to have been caught. Co-operating fully with the investigation, he was sentenced to just a year in prison, where he earned the nickname ‘Picasso’ by doing portraits of other inmates in return for phonecards.

After leaving prison, he vowed never to pick up a paintbrush again. Until he received a phone call from Jonathan Searle, one of the Scotland Yard detectives who had investigated the case.

Searle offered him £5,000 to paint a portrait of his family – and so he began his own legitimate business, selling paintings across the world and giving lectures on the business of art fraud.

He has since admitted that, from time to time, he still sees one of the forgeries on display in a museum or gallery, but he keeps quiet about those works which escaped the police net. This is partly to avoid disappointing innocent collectors who have paid thousands of pounds for them – but also because he fears that they might be destroyed.

And after all, as long as they remain on display, the most unwilling forger of all time can still claim his own unique place in the history of art.

This Post Has 0 Comments