Realistic Schools: Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood

- Dante Gabriel Rossetti.

The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (also known as the Pre-Raphaelites) was a group of English painters, poets, and critics, founded in 1848 by William Holman Hunt, John Everett Millais and Dante Gabriel Rossetti. The three founders were soon joined by William Michael Rossetti,James Collinson, Frederic George Stephens and Thomas Woolner to form a seven-member “brotherhood”.

The group’s intention was to reform art by rejecting what they considered to be the mechanistic approach first adopted by the Mannerist artists who succeeded Raphael and Michelangelo. They believed that the Classical poses and elegant compositions of Raphael in particular had been a corrupting influence on the academic teaching of art. Hence the name “Pre-Raphaelite”. In particular, they objected to the influence of Sir Joshua Reynolds, the founder of the English Royal Academy of Arts. They called him “Sir Sloshua”, believing that his broad technique was a sloppy and formulaic form of academic Mannerism. In contrast, they wanted to return to the abundant detail, intense colours, and complex compositions of Quattrocento Italian and Flemish art.

The Pre-Raphaelites have been considered the first avant-garde movement in art, though they have also been denied that status, because they continued to accept both the concepts of history painting and of mimesis, or imitation of nature, as central to the purpose of art. However, the Pre-Raphaelites undoubtedly defined themselves as a reform-movement, created a distinct name for their form of art, and published a periodical, The Germ, to promote their ideas. Their debates were recorded in the Pre-Raphaelite Journal.

Beginnings of the Brotherhood

The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood was founded in John Millais’s parents’ house on Gower Street, London in 1848. At the initial meeting, John Everett Millais, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, and William Holman Hunt were present. Hunt and Millais were students at the Royal Academy of Arts. They had previously met in another loose association, a sketching-society called the Cyclographic Club. Rossetti was a pupil of Ford Madox Brown. He had met Hunt after seeing his painting The Eve of St. Agnes, which is based on Keats’s poem. As an aspiring poet, Rossetti wished to develop the links between Romantic poetry and art. By autumn, four more members had also joined, to form a seven-member-strong Brotherhood. These were William Michael Rossetti (Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s brother), Thomas Woolner, James Collinson, and Frederic George Stephens. Ford Madox Brown was invited to join, but preferred to remain independent. He nevertheless remained close to the group. Some other young painters and sculptors were also close associates, including Charles Allston Collins, Thomas Tupper, and Alexander Munro. They kept the existence of the Brotherhood secret from members of the Royal Academy.

Early doctrines

The Brotherhood’s early doctrines were expressed in four declarations:

- to have genuine ideas to express;

- to study Nature attentively, so as to know how to express them;

- to sympathise with what is direct and serious and heartfelt in previous art, to the exclusion of what is conventional and self-parodying and learned by rote;

- and, most indispensable of all, to produce thoroughly good pictures and statues

These principles are deliberately non-dogmatic, since the Brotherhood wished to emphasise the personal responsibility of individual artists to determine their own ideas and methods of depiction. Influenced by Romanticism, they thought that freedom and responsibility were inseparable. Nevertheless, they were particularly fascinated by medieval culture, believing it to possess a spiritual and creative integrity that had been lost in later eras. This emphasis on medieval culture was to clash with certain principles of realism, which stress the independent observation of nature. In its early stages, the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood believed that their two interests were consistent with one another, but in later years the movement divided and began to move in two directions. The realist-side was led by Hunt and Millais, while the medievalist-side was led by Rossetti and his followers, Edward Burne-Jones and William Morris. This split was never absolute, since both factions believed that art was essentially spiritual in character, opposing their idealism to the materialist realism associated with Courbet and Impressionism.

In their attempts to revive the brilliance of colour found in Quattrocento art, Hunt and Millais developed a technique of painting in thin glazes of pigment over a wet white ground. They hoped that in this way their colours would retain jewel-like transparency and clarity. This emphasis on brilliance of colour was in reaction to the excessive use of bitumen by earlier British artists, such as Reynolds, David Wilkie and Benjamin Robert Haydon. Bitumen produces unstable areas of muddy darkness, an effect that the Pre-Raphaelites despised.

Public controversies

The first exhibition of Pre-Raphaelite work occurred in 1849. Both Millais’s Isabella (1848–1849) and Holman Hunt’s Rienzi (1848–1849) were exhibited at the Royal Academy, and Rossetti’s Girlhood of Mary Virgin was shown at the Free Exhibition on Hyde Park Corner. As agreed, all members of the Brotherhood signed works with their name and the initials “PRB”. Between January and April 1850, the group published a literary magazine, The Germ. William Rossetti edited the magazine, which published poetry by the Rossettis, Woolner, and Collinson, together with essays on art and literature by associates of the Brotherhood, such as Coventry Patmore. As the short run-time implies, the magazine did not manage to achieve a sustained momentum. (Daly 1989)

Christ In the House of His Parents, by John Everett Millais, 1850.

In 1850 the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood became controversial after the exhibition of Millais’s painting Christ In The House Of His Parents, considered to be blasphemous by many reviewers, notably Charles Dickens (Dickens considered Millais’ Mary to be ugly. Interestingly enough, Millais had actually used his sister-in-law Mary Hodgkinson as a model for the Mary in his painting). Their medievalism was attacked as backward-looking and their extreme devotion to detail was condemned as ugly and jarring to the eye. According to Dickens, Millais made the Holy Family look like alcoholics and slum-dwellers, adopting contorted and absurd “medieval” poses. A rival group of older artists, The Clique, also used their influence against the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. Their principles were publicly attacked by the President of the Academy, SirCharles Lock Eastlake.

Following the controversy, Collinson left the Brotherhood. They met to discuss whether he should be replaced by Charles Allston Collins orWalter Howell Deverell, but were unable to make a decision. From that point on the group disbanded, though their influence continued to be felt. Artists who had worked in the style still followed these techniques (initially anyway) but they no longer signed works “PRB”.

Ophelia, by John Everett Millais

However, the Brotherhood found support from the critic John Ruskin, who praised their devotion to nature and rejection of conventional methods of composition. The Pre-Raphaelites were influenced by Ruskin’s theories. As a result, the critic wrote letters to The Times defending their work, later meeting them. Initially, he favoured Millais, who travelled to Scotland with Ruskin and Ruskin’s wife, Effie, to paint Ruskin’s portrait. Effie’s increasing attachment to Millais, among other reasons (including Ruskin’s non-Consummation of the marriage) created a crisis, leading Effie to leave Ruskin, which caused a public scandal. Millais abandoned the Pre-Raphaelite style after his marriage, and Ruskin often savagely attacked his later works. Ruskin continued to support Hunt and Rossetti. He also provided independent funds to encourage the art of Rossetti’s wife Elizabeth Siddal.

Later developments and influence

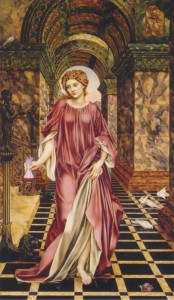

Medea by Evelyn De Morgan, 1889, inquattrocento style

Artists who were influenced by the Brotherhood include John Brett, Philip Calderon, Arthur Hughes,Gustave Moreau, Evelyn De Morgan, Frederic Sandys and John William Waterhouse. Ford Madox Brown, who was associated with them from the beginning, is often seen as most closely adopting the Pre-Raphaelite principles.

After 1856, Rossetti became an inspiration for the medievalising strand of the movement. His work influenced his friend William Morris, in whose firm Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co. he became a partner, and with whose wife Jane he may have had an affair. Ford Madox Brown andEdward Burne-Jones also became partners in the firm. Through Morris’s company the ideals of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood influenced many interior designers and architects, arousing interest in medieval designs, as well as other crafts. This led directly to the Arts and Crafts movement headed by William Morris. Holman Hunt was also involved with this movement to reform design through the Della Robbia Potterycompany.

After 1850, both Hunt and Millais moved away from direct imitation of medieval art. Both stressed the realist and scientific aspects of the movement, though Hunt continued to emphasise the spiritual significance of art, seeking to reconcile religion and science by making accurate observations and studies of locations in Egypt and Palestine for his paintings on biblical subjects. In contrast, Millais abandoned Pre-Raphaelitism after 1860, adopting a much broader and looser style influenced by Reynolds. William Morris and others condemned this reversal of principles.

The movement influenced the work of many later British artists well into the twentieth century. Rossetti later came to be seen as a precursor of the wider European Symbolist movement. In the late twentieth century the Brotherhood of Ruralists based its aims on Pre-Raphaelitism, while the Stuckists and the Birmingham Group have also derived inspiration from it.

The Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery has a world-renowned collection of works by Burne-Jones and the Pre-Raphaelites that, some claim, strongly influenced the young J.R.R. Tolkien, who would later go on to write his novels, such as The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings, with their influence taken from the same mythological scenes portrayed by the Pre-Raphaelites.

In the twentieth century artistic ideals changed and art moved away from representing reality. Since the Pre-Raphaelites were fixed on portraying things with near-photographic precision, though with a distinctive attention to detailed surface-patterns, their work was devalued by many critics. Since the 1970s there has been a resurgence in interest in the movement.

Source: en.wikipedia.org

This Post Has 0 Comments