Secrets of Vermeer’s painting technique.

Vermeer’s painting technique: Underpainting

After the initial outline drawing was completed Vermeer began the underpainting, one of the most important stages in his working procedure. Without a thorough knowledge and mastery of the underpainting technique, many of the artist’s complex compositions, accurate depiction of light and chromatic subtleties could not have been easily achieved.

Adoration of the Magi by Leonardo da Vinci

Underpainting, or “dead color” as it was called in Vermeer’s time, is rarely practiced today. For the last century, most artists have simply begun painting directly on the canvas with full color surpassing the underpainting stage entirely. Therefore, neither the function or the practice of underpainting is well understood. In its simplest terms, underpainting is a monochrome version of the final painting which fixes the composition, gives volume and substance to the forms, and distributes darks and lights creating an effect of illumination. The lack of color probably explains the word “dead” in the term “dead painting.” In the17th c. underpainting appears in various forms, sometimes as loose monochrome brushwork and sometimes as an assembly of evenly blocked-out “puzzle pieces” of different colors. Painters generally used warm browns, black and ochers and at times white in underpainting. Color was then applied over the underpainting only when it was thoroughly dry.

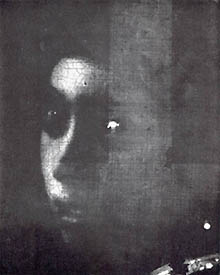

Radiograph of Girl with a Pearl Earring

Both the initial drawing of the Virgin and the beginnings of the underpainting can be clearly seen in an unfinished work by Leonardo (right). Vermeer’s underpanting may have been different from Leonardo’s since it is certain that Vermeer made use of white lead at this stage. It cannot be ascertained if Vermeer defined his underpainting as accurately as that of Leonardo.

With a minimum of effort the artist was able to envision quite accurately the totality and the complexities of his pictorial idea. He could observe the defective parts of the painting and correct them with relative ease for it is far easier to model with a few neutral tones than with more complex color mixtures. Even broad areas of the canvas which seemed too dark could be easily worked up and lighter ones darkened. Pigment used and degree of finish varied from school to school and even painter to painter.

Rembrandt and Rubens in particular are know to have used underpainting very effectively and their methods are often cited as examples. A few surviving underpaintings by Rembrandt can be appreciated as a work of art in themselves.

Underpainting was not only a rapid and economical way to envision and correct often elaborate compositions, it also aided the painter in creating a number of optical effects that cannot be achieved by direct painting with color as well.

It seems certain that the underpainting was a fundamental step in Vermeer’s creative process. Laboratory analysis demonstrates that he made many major and minor corrections in the placement and size of the objects found in his compositions. Chairs, maps, framed paintings, musical instruments, baskets, a standing cavalier and even a dog can no longer be seen where they were originally represented. Vermeer probably painted them out in the underpainting stage having seen that they did not create the desired effect or that they were distracting to the central theme of the painting. He changed the positions of arms and fingers to create precisely the gesture he desired, edges of maps were moved to the left or right to add stability to the composition and the contours of the the young women’s garments were altered to make them more elegant and fluid, shadows too were lightened or darkened, all depending of the immediate visible effect that the underpainting produced.

Lawrence Gowing, a painter and one of the most penetrating of Vermeer scholars, believes that an x-ray photograph of the face of the Girl with a Pearl Earring constitutes evidence of the artist’s painting method. X-rays images reveal the presence of lead, which is the primary component of lead-white, the principal white pigment used by painters in Vermeer’s time. Gowing assumes that the white areas of the image correspond the underpainting stage and was a direct transcription of the incidence of light on the screen of the camera obscura. Particularly suggestive of the camera obscura’s effect is the perfectly spherical highlight of the pearl earring which has been altered in the final version, the same goes for the dim highlight of the eye to the right hand side of the painting. Gowing believes that “the artist, evidently proceeded, in finishing the picture, to mediate between objectivity and convention.” 1 Since the x-ray image only reveals the presence of the heavier lead white and the remaining areas are registered as black, it tends to produces an exaggerated effect of contrast.

Gowing’s idea has been corroborated by Phillip Steadman’s more recent hypothesis that Vermeer may have used the camera obscura not only to trace the projected camera obscura image on the canvas, but also to paint in strict correlation with camera obscura image always close at hand.

In the Girl with a Pearl Earring the illuminated portions of the skin have been underpainted in a warm cream tone over the darker ground. This layer served as a basis for subsequent applications. Since even the most opaque pigments are never entirely covering, it is very difficult to contemporarily obtain precise modeling and accurate color when painting directly over a dark ground.

The darker areas of the flesh were underpainted with transparent layers of black mixed with ochre or umber. Red madder, vermilion and red ochre seems to have been used in the shadowed areas of the nose and in the lips. The dark shadowed areas of the turban were also painted with transparent layers of black and umber. The monochromatic finished underpainting probably lacked the more subtle transitions of the chiaroscuro although the physiognomy and expression of the face was probably very well defined.

Unfortunately, while laboratory analysis can identify the existence of Vermeer’s underpainting, its exact nature cannot be determined in great detail since is as its name implies, it lies under other layers of paint. A relatively new technique called radiographic photography is able to evidence black pigment which is under other layers of paint. Although it has been extremely valuable as a method for analyzing the nature of old masters underpainting, the picture it produces is not entirely accurate since shades of browns (umber usually) which are not revealed by the method, were very often mixed in varying proportions with black.

However, a few excellent examples of unfinished works of art that reveal quite accurately standard underpainting procedures have survived and Vermeer’s methods probably did not vary a great deal from them. It is believed that artists once kept a number of underpaintings in their studio waiting for clients’ interest before completing the painting in color.

This Post Has 0 Comments