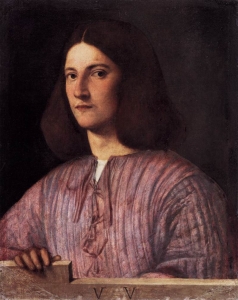

Hot to paint like Titian. The “Venetian Method”

Titian and Giorgione were foremost among the pioneers of what we now call the Venetian Method of oil painting. The Venetian Method, or Venetian Technique, borrowed heavily from the Flemish Method, which saw the application of transparent glazes for the shadows, greater contrast between dark and light areas, and opaque highlights. The Venetian Method, however, deviates in some key areas, adding its own take on the Flemish process.

Titian and Giorgione were foremost among the pioneers of what we now call the Venetian Method of oil painting. The Venetian Method, or Venetian Technique, borrowed heavily from the Flemish Method, which saw the application of transparent glazes for the shadows, greater contrast between dark and light areas, and opaque highlights. The Venetian Method, however, deviates in some key areas, adding its own take on the Flemish process.

While the glossy finish of the Flemish Method was ideal for small wood panels, on large paintings it was distracting and decidedly “overkill”; ergo, Titian refined the painting process to produce a less reflective surface. Most probably, he cut out sheen-enhancers like polymerized oils, balsams, and resins, and replaced them with simpler paints that relied on raw oil only. He also discovered that stiff, hog bristle brushes were more applicable to work done on rough textured canvas.

The large, stiff brushes and the tooth of the canvas, however, made it harder to achieve the sharp edges which occur naturally in the Flemish Technique. Titian, and presumably Giorgione, found the softer edges more appealing, fortunately, and rather than fight them, the artists embraced the soft look. Rather like in a macro photograph today, certain small areas could be selectively enhanced to create a particular area of focus.

Their technique also made paintings seem more lifelike, as the results were closer to what our eyes would see, as opposed to the stark, hard edges of the Flemish Method. Titian is thought to have used an opaque underpainting, leaving the edges soft to allow for more flexibility with later adjustments. This underpainting was let dry for some time (while the artist often worked on other pieces), and was then painted over in colour, beginning with transparent glazes applied to the shadow areas (a key practice of the Flemish Technique), and then built up with more opaque tones meant to create the effect of highlights.

In the Venetian Method, colour is generally applied over the underpainting first as transparent glazes. The wet paint was then worked either until the artist was satisfied, or until the paint became slightly tacky, whereupon it had to be allowed to dry completely before the artist continued on. This process was repeated over and over until the artist deemed the work complete.

Some time during the Renaissance, it was found (we are not sure by whom) that a light, opaque tone, which was made slightly transparent by the addition of a touch of oil mixed in and/or a bit of oil thinly applied overtop the paint via a stiff brush, produced an appealing effect over darker areas. This is today called a scumble, and is known for making the texture of skin appear softer, resulting in the glowing skin seen on women and young people in these old paintings. It can also be used to create the illusion of atmospheric density over distance, or atmospheric perspective. Early painters had a much more limited range of colours than we have today, so they relied more heavily on such effects to lend depth to their work.

This Post Has 1 Comment